History Ch 6

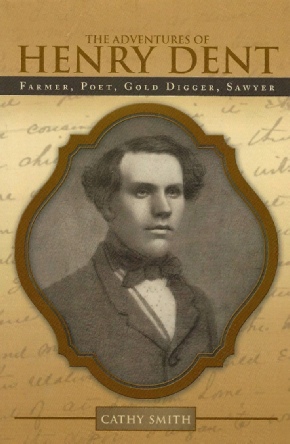

Henry Dent

An intriguing inscription on a memorial stone in Bolton church yard led Cathy Smith to investigate the life of farmer’s son Henry Dent who died in Van Diemen’s Land in January 1854, aged 27. How and why had he travelled so far from home? Using many of Henry’s own words from his poems and letters, Cathy has reconstructed Henry’s brief but adventurous life.

|

Published by AuthorHouse

Available to purchase via www.authorhouse.co.uk, www.amazon.co.uk Copyright: 2010 Cathy Smith The Adventures of Henry Dent By Cathy Smith |

“The First Aspirations of Thought written for Amusement and doomed to the flames.” These words were written by 20 year old farmer’s son Henry Dent of Bolton in Westmorland, England, in the year 1847 on the first page of a notebook in which he painstakingly wrote out poems of his own composing. Little did he know that only a few years later it would be he who perished in flames, whilst the notebook survived in an attic for over a hundred years.

Henry’s death is commemorated by a tombstone stating that he died at Flight’s Bay, Van Diemen’s Land on January 11th 1854, aged 27 years, and was interred at Franklin. How did he come to die so far away from home? Thanks to members of his family, many of his letters home have been preserved, and from these we can piece together his short but adventurous life.

In 1852 Henry decided to emigrate to Australia to dig for gold. He was to sail from Liverpool on the SS Serampore, and writing before the voyage got under way, he was full of praise for onboard arrangements:

We are very comfortably situated and are just getting arranged into messes of a dozen each to sit down to table together. We have a messman at the head of each table who deals out an equal quantity of what is laid before us. We have about a dozen biscuits brought to the table of the size of a good bason top and half an inch thick. Cans of coffee are brought and the allowance of butter. He with a table knife places the butter upon the biscuit and the parties spread it themselves. Two cups of coffee is the allowance. We don’t allow any to leave table till all have done and so we avoid confusion by another stepping in. By this system the messman and his party all leave table together. Yesterday we dined on salt beef, soup and half a biscuit each. On Saturday we had fresh beef to dinner and there was more than required. We breakfast at 8 in the morning, dine at 12.30 and tea about 6.

Conditions deteriorated as the voyage progressed, but the ship arrived in Port Philip without any passengers falling sick and Henry and his companion Henry Richardson found lodgings in Lonsdale Street, Melbourne before setting off to the ‘diggings’. With help from a family friend, Mr Palmer of Kyneton, they travelled to Fryers Creek, Mount Alexander.

In a letter written in December, Henry describes their neighbours:

We are in good society, comparatively speaking and surrounded by kind neighbours. Our nearest neighbour is a gentleman from Northumberland of the name of Archibald who left England in 1841 and has now a sheep station at Wimmera 200 miles up the country. His sons are now up shearing the sheep. They are first rate neighbours and I sometimes go and hold a yarn with him. Another neighbouring tent is inhabited by a family of respectable persons named Adcock. They left Cumberland about 2 years ago and have been keeping a grocer’s shop in Melbourne till last Summer. They came up to the diggings and have done pretty well. Another family of Watsons reside in our row who left Cumberland a month or two before I left home. Then there is Mr Palmer’s tent containing Robert, John and William together with two of the Shearmans of Orton. The old gentleman Joseph Shearman was taken by the dysentery and was obliged to be taken down to Kyneton last week. We heard yesterday that he is no better and his two sons are off to see him. Two or three of the Palmers generally stay at the diggings about three months each end of the year.

The life of a digger was very hard. First of all he had to purchase from the Commissioner a licence “to dig, search for and remove gold from the Crown Lands of Victoria”. This cost 30 shillings a month but without it, one could be fined a considerable amount. It entitled the holder to a plot measuring just 8ft x 8ft in which he might dig down anything up to about 50 or 60 feet in the search for gold. Labour such as this required considerable physical strength, and some men soon gave up. If they had heard tales of the early days when gold dust could be found in the roots of the grass or when nuggets could be found lying in the beds of the streams, this hard labour would have been even harder to bear.

Many who are well qualified to handle a pick and shovel have been allured from their writing desk or counter at home by the hope of soon picking up on the diggings what will make them independent of work for the whole of their after life. Some of these are discouraged at first sight of the diggings and dare not face the labour requisite to obtain the gold. Others begin to dig and I have sometimes been amused to see them making their first efforts. They use the pick something like a young bird it’s wings – very feebly. Some of these after sinking a few blank holes throw down the pick in despair and betake themselves to work for which they are more adapted. Others return to England, very likely with a bad report of the country when in fact the country is not to blame, but they are not adapted to its wants.

Fortunately when in difficulty Henry could rely on the hospitality offered by Mr Palmer who was apparently so generous that

Some indeed he has killed with kindness or in other words he has given them the requirements of Nature and entertainments of his house, refusing to receive remunerations till they sometimes passed his house without calling, when they would have been glad to have lodgings with him, if he would make a charge for it or receive a voluntary gift, but knowing that he has many visitors and that if they called he would receive no pay, they have chosen to travel on a little further. The old man seems to be disposed to do a good turn to any of his old countrymen or acquaintances and he is now in circumstances that he can well afford it. When we came up, the carriage of luggage was extremely high. Mr Palmer being gone to town I wrote him a note requesting him to bring up a chest containing some clothes of Mr Richardson’s and my own. In case he should be too hard loaden I requested him to get it to some drayman in whom he had confidence and I would pay him on his return. On being down since his return I offered to pay the carriage. “Not one farthing” said he. “If I charged you anything for a job like that I would never forgive myself while I live. My family received many favours from your father in past times and I think of such things.” He then told me that until I got settled I was to make his house my home and I should always be welcome. If at the diggings or anywhere else in the colony I should lose my health I was to make the best of time in getting to his house and they would do all for me that laid in their power.

No doubt this assurance as to his physical welfare would be of great comfort to Henry’s mother at home in Bolton, but Henry is also at pains to reassure his Methodist father on the question of his spiritual health. He seeks to justify his decision to seek gold, as many religious people were of the view that this was an “unpardonable sin”. He thinks such people would lose their prejudices if only they could visit the diggings, where they would find

men of all classes of society and of nearly all trades and professions from the weaver who has left his loom to the lawyer who has quitted his wig. They’ll find men of reputable character and sterling principle who have taken up the digger’s pick and shovel and are anxious to make their fortune and “gather geese”

Not for to hide it under a hedge

Or for a State attendant

But for the glorious privilege

Of being independent.

And some I have no doubt from even higher motives than this, that they may be useful to their day and generation in dispelling darkness, ignorance and crime from the face of society both in their adopted country and the more privileged but still poor man’s face-grinding England. It is true that there are bad characters on the diggings but not in so great a proportion as some are led to suppose. What part of the colonies would these individuals go to in order totally to escape bad company? May I not ask what part of England they could go to where every face they saw was unknown to them and still be confident they were in good company. In no place could they be sure of it. How much less then can they expect always to be in good company in a colony surrounded by penal settlements – a place not only having to contend with its own natural proportion of crime but with a hoard of profligates exported from England under the abominable system of conviction. These men are all that are to be feared upon the diggings and at present I believe less crime is committed upon the diggings than in Melbourne and on the road.

Since I commenced we have been working the same hole and it yields us perhaps an ounce and a half of gold per day between us and so long as it will yield an ounce a day we will continue to work it, but if it falls under we will look out for another place.

However, when Henry Richardson contracted dysentery, the friends decided to leave Fryers Creek and try another enterprise. Although there was money to be made from farming, Henry was not tempted to buy a farm, although by this time he had a decent ‘competency’ of £200 from his gold. He chose to go over to Van Diemen’s Land, writing to his mother in March 1853:

I had two or three motives in coming here. One was for a little recreation; another to see the place and ascertain how the prisoners were treated, who have been sent from England for their country’s good, and third and last to trade a little in Van Demonian produce.

On the first point, he says the island is “a beautiful place, diversified with hills and vallies, woods, rivers and plains and is a most salubrious climate. The Derwent is the finest river I ever saw and a splendid harbour at Hobart Town into which the largest vessel in the world might sail with ease, the river being 2 or 3 miles wide.“ The green hills rising to the peak of Mount Wellington which towers over the little harbour town, the blue of the river and the invigorating breezes blowing from the Southern Ocean must have been quite a tonic after the scorching dry conditions at the diggings during the mainland Summer. This Autumn weather reminded Henry of home most poignantly and he wrote six letters home between March and November that year.

Henry argues that it is not the fault of Van Diemen’s Land that it is perceived to be a jail,

.. it is not her fault. She must thank the virtuous and humane England for that. And though I never had any ambition to go to jail while at home, when I got out into Australia I confess I thought I should like to go to jail, of course not on the penetensiary but to see England’s great prison and observe the treatment of the unfortunate inmates. Did I say unfortunates – there are some who have had the sentence of “hard labour” passed upon them “for the period of their natural life” who are now rolling in luxury, driving their carriage and have all that the heart could wish. Verily I believe they would have been more punished by being set at liberty at home where a man must work hard for all he gets.

Trading took Henry out of Hobart and into the interior of the island. He describes to his mother a particularly rough journey to a place 35 miles from Hobart, when he was grateful to a family called Weeding who farmed near Greenponds.

One gloomy morning I mounted the coach at 6 o’clock to go into their neighbourhood. We had not travelled far when the rain began to fall very heavily and I felt the difference of a stage coach to a railway carriage in the exposure to the inclemency of the weather. When we arrived at Greenponds I had about 4 or 5 miles to travel over the steep hills and through rough and long grass and what rendered the case worse I nearly lost the heel of one of my boots. However, on arriving at the Hunting Ground Mrs Weeding gave me a hearty welcome though I could by no means be a pleasant guest.

The friends then saw an opportunity to start a timber cutting business on the Huon River, as timber products were in great demand on the mainland. On September 11th Henry wrote to his mother about this new location:

Mr Richardson and I are at present living in a hut on the banks of the River Huon at Flights Bay where the river may be said to merge into an arm of the sea for vessels of almost any tonnage might with perfect safety come up thus far, in full sail. This morning the reflected beams of the sun make a part of this bay appear like a sheet of glass. Another part has a gentle curl playing up it with the morning breeze. Here and there its surface as a mirror reflects the clouds and the surrounding woodland hills. This as you are aware, is a Winter’s morning, yet all around is clad in green. The brushwood assumes a thousand different forms. Some of the shrubs would grace a gentleman’s pleasure ground, but although they are strowed about in apparent confusion, yet to me they have a charm of which they would be deprived were they placed in that artificial capacity. They have here all that luxuriousness with which a bounteous Nature can adorn them. The other day Nature seemed convulsed – one squall of wind after another howled through the forest, the Bay was all emotion, the rain fell in torrents and the peals of distant thunder were frequent. Now all is calm, serene and beautiful, and the little birds, though they cannot sing like the thrush, the linnet or the nightingale are manifesting their joy in the best and sweetest strains with which Nature has endowed them.” He describes the tall trees “whose aspiring trunks shoot up to a height seldom thought of and more seldom realised in England.

However this idyll was not to last, and it was Henry Richardson who described the fateful day – January 11th 1854:

At 1 o’clock, the day being warm with a hot wind, we had been bathing in the bay. We then had dinner. About 3 o’clock we commenced to saw. In about 10 minutes after this the wind began to blow a complete hurricane. The fire had been burning on the ranges for a day or two. It now began to approach us with the most alarming rapidity; so soon as we became conscious of our danger we threw a few pieces of timber from the pit which was likely to ignite, and ran into the hut, having thrown out a few articles, the whole of which did not occupy more than two or three minutes. He told me to run with the bedding to the beach and try to save it. I immediately did as required and in less than half a minute deposited it there. I then attempted to return, as he had not followed me as I expected, but found it impossible to do so as the fire was already across the path by which I had come. So soon as I durst venture for the fire and smoke, though still at imminent danger from falling trees and branches, I did so, when I was horror struck to find him lying in the middle of a cart road, not having got more than 50 yards from the hut. He must have been choked by the smoke. The smoke from the underwood which is green and full of gas is so strong that anyone breathing it is almost immediately suffocated.

Henry’s body was taken to the town of Franklin, about 12 miles away, for an inquest and burial. The page recording his death states as cause of death ‘Burnt to death by Bush Fire’ and there are five similar entries on the same page, two other ‘Labourers’, one ‘Labourer’s wife’ and two children.

It would have been June or July 1854 before news of this terrible disaster reached Bolton. How would parents feel to know that for the last six months when they thought that their son was happy and prospering in the new country, he had in fact been dead and buried? What to do, how to tell your friends and neighbours? How to remember your firstborn son? At some point the Dents caused a memorial stone to be erected in the churchyard, so that there was at least a place where his memory could be honoured. A hundred and fifty years later its intriguing inscription and the careful preservation of Henry’s letters has led to the retelling of his fascinating story.

Email: cathys55@hotmail.com